I recall the exact moment when I decided to raise Dubsie in Spanish. She and I were walking on 5th Street, or rather “walking,” since stepping out with an 18-month old is an exercise in going nowhere. I sing-songed for her to come along, and she tripped a few steps before being transfixed by the next fascinating object, in this case a half-brick lying on the curb.

I recall the exact moment when I decided to raise Dubsie in Spanish. She and I were walking on 5th Street, or rather “walking,” since stepping out with an 18-month old is an exercise in going nowhere. I sing-songed for her to come along, and she tripped a few steps before being transfixed by the next fascinating object, in this case a half-brick lying on the curb.

As she wrapped her hands around and tried to lift it (like me trying to carry a refrigerator), I thought about my friend Russ. He had recently closed down his life in Washington, D.C and jetted off to live in Italy for a year with his wife and two young children. He is from California like me, but loves Italy so much that he gave his children Italian names and speaks to them in a nonstop stream of passionate but not particularly skilled Italian. Russ hoped to live in the Ladin region, where the local schoolchildren are taught not one, not two, but four languages — Italian, German, English and the local tongue called Ladin. That’s how committed Russ is to exposing the next generation to other languages.

As I stood there watching Dubsie, I thought about the three years of Spanish I’d taken in high school with Mrs. Livingston, reciting alongside my bored classmates about how mi abuela makes tamales muy buenas, and the three months in college I spent on an exchange program in Mexico City, most of it at la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México where they tossed us mercilessly into college-level anthropology and history classes, led by Profesor Álvarez, who explained the origin of the Olmec people and detailed the numerous and doomed uprisings of the peasants of the Yucatán, and where for homework I read the entirely of Octavio Paz’s El Laberinto de la Soledad, and on the weekend I took a bus to the ruins of Tenochtitlán in the company of my host brother, Antonio, speaking Spanish all day until my brain was dull and tongue sore, and in the end was sent off to do a month-long field study in Chiapas, in El Triunfo, a mountainous cloudforest near the border with Guatemala, where I was supposed to study la fauna y la flora de la selva, but with no idea what that meant I whiled a few days hiking with rangers looking for quetzal, the emerald long-tailed bird of the jungle, and one night went to a house party of the rangers, where still in their beige button-up shirts they passed around a big red plastic jug full of mezcal, a horrible, throat-scalding homebrew that tasted like cigarettes, and I wound up arm-wrestling a bandy little ranger named Hugo before stumbling back through the village of Santa Rita, in the dark past the huts and the coffee plants to my living quarters, the communal meeting house, also called the ejido, where I slept on benches rafted together and listened to rats scurry in the eaves, and stumbled hung-over in the morning out a doorway so low that I cracked my head on it, to the great amusement of the children who gathered to laugh and catcall as the giant gringo took a bucket shower, his lathered head towering above the stall walls, and on Sunday we played basketball, me and nine little Indians, short natives whose bloodlines had barely been touched by the conquistadores and who called out plays to each other in their native tongues of Tzeltal and Tzotzil, and on the regretful day it came time to return to the state capital, Tuxtla Gutierrez, I hitched a ride with a farmer in his pickup truck whose radio was tuned to news of the first Iraq war, which was just then beginning, and in his cowboy hat the farmer turned to me, as the announcer intoned the name of a dictator with the strange name of Saddam Hussein, and informed me that este Jose es un mal hombre.

Maybe I could teach my daughter a language too.

“Dubsie!” I announced. “Vámonos!”

She continued playing with her brick.

She continued playing with her brick.

Next I would need to tell her to put down the brick and come with me. “Dubsie, ¡deja la…” what was the word for ‘brick’ again? “…ladrón y fui conmigo!”

Later, when I researched it, I discovered that I’d told her put down the burglar and I went with me. Not that Dubsie spotted the error. She was bending down and seeing if, since she couldn’t lift the brick, maybe she could eat it.

“Dubsie, ¡no pone el ladrón en el bocado!” I said, louder this time, because that always helps when someone doesn’t understand your language.

Eventually I resorted to the universal language — bodily force — and separated her from the brick and carried her back to the house. Dinnertime. I installed Dubsie in her high chair and announced our new semantic regime. From now on, I told my wide-eyed daughter, we would speak in Spanish about eating in Spanish. ¡Espanol! Dubsie, let’s comer (eat) your arroz (rice) with una cuchara! (spoon!) But then I was stumped. What is the word for bowl? I can’t remember. How about tray? I don’t think I ever learned that one. Or safety buckle? Or mouthful?

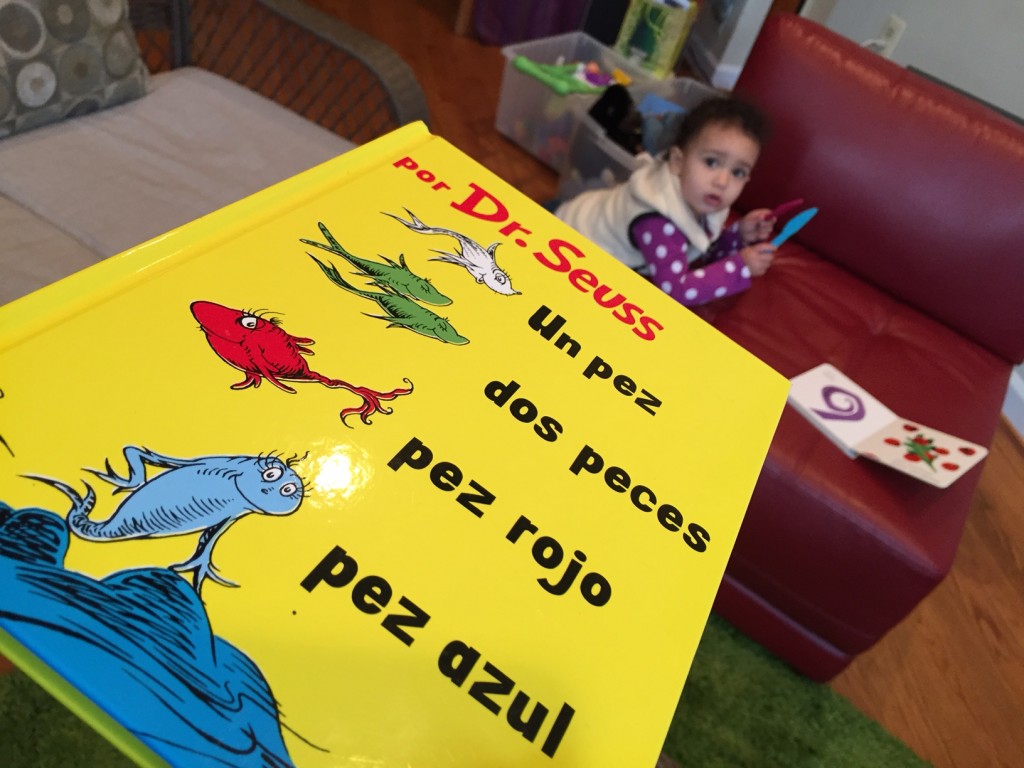

We finished eating and I carried her over to the couch for some easier Spanish. I determined I would do a simultaneous English-Spanish translation of one of her toddler books. How hard could it be? I picked out Baby Animals, by Gyo Fujikawa.

Wooly lambs hop, skip and jump, the book read. Good Lord, I don’t know how to say a single word of that in Spanish. So I flipped past that one to Downy ducklings waddle and swim. Well, I know the word for swim. “¡Nadar!” I hollered enthusiastically to Dubsie. She seemed alarmed that I was so worked up about ducklings.

The problem was that neither Mrs. Livingston nor Profesor Álvarez had taught me a fraction of the universe of words one needs to navigate the world.

Then it was upstairs to change her…dammit, what’s the Spanish word for diaper? I should know this! It’s printed on the dumb box! I ended up wiping pee off my hands and looking it up on Google. I began to question whether I actually knew Spanish at all.

This is the world of a gringo teaching Spanish to a toddler, constantly running into linguistic box canyons. It has been a humbling experience. My supposed proficiency in Spanish had foundered, and I have been marooned in an endless sea of objects and activities I can’t name.

But I have stuck with it. Dubsie has been enormously patient (a kind word for clueless), as her daddy re-learns Spanish while she acquires the rudiments of language. It has been an often discouraging road, and there have been many instances where I have stammered out phrases that to a native speaker would be barely coherent, like “Dubsie, no to touch the toilet because someone pooping in it was!”

And Dubsie is getting the hang of it, absorbing every syllable around her and Spanish along with it. When she babbles it’s doubly hard to understand because I don’t know which language she’s mangling. When her head gets heavy she asks to be put in her cama (crib), and she loves to dibujar (draw) on papel (paper) with her crayons (crayons). We get a call-and-response thing going.

And Dubsie is getting the hang of it, absorbing every syllable around her and Spanish along with it. When she babbles it’s doubly hard to understand because I don’t know which language she’s mangling. When her head gets heavy she asks to be put in her cama (crib), and she loves to dibujar (draw) on papel (paper) with her crayons (crayons). We get a call-and-response thing going.

As I’m peeling off a big, wet puffy diaper, I say, “Dubsie, tienes un pañal…” (you have a diaper that’s…)

“…gigante!” (ginormous!) she cries.

“Y….” (and…) I say.

“…apestoso!” (stinky!) she yells.

I get interesting reactions when I divulge that I’m raising her in Spanish. (“Why?” one Puerto Rican co-worker asked me incredulously.) But most are more subtle in their judgments. They glance at me, with my freckled pale arms and giant forehead, and silently confirm the obvious, which is that this gentleman has not a drop of Latin blood in him.

But I did tell one friend whose reaction was most kind. She said in a gentle but very matter-of-fact way, “So you’re going to raise your daughter with bad Spanish.”

“Yes,” I said with a slow nod. “I’m going to raise her speaking bad Spanish.”

This is your fate, Dubsie. You’re dad is going to raise you speaking not quite the right words, in a gringo accent, and with sloppy grammar. In this global polyglot world, I figure that will set you up just fine.

Chistoso!